How persistent is the inference cost burden?

RL scaling might be better than it looks, and inference costs to reach a capability level fall fast

This post is part of Epoch AI’s Gradient Updates newsletter, which shares more opinionated or informal takes on big questions in AI progress. These posts solely represent the views of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect the views of Epoch AI as a whole.

Toby Ord has written a thoughtful post on how RL and inference compute scale for frontier AI models.

As I understand it, the core of his argument is

(1) RL scaling primarily bears fruit by enabling models to productively use longer outputs, which means you need to scale inference compute to realize the gains

(2) RL scaling itself delivers poor returns, requiring roughly 10,000x more compute to match what 100x more inference provides.

Combined with the fact that inference costs are per-use and can’t be amortized like training costs, this paints a picture of a significant and persistent economic burden as we shift away from pretraining scaling.

There’s a lot I agree with in Toby’s analysis, and I find the framing useful. However, I think both claims above may be overstated. On (1): even though inference costs are per-use, the dollar cost to reach a given capability level falls rapidly over time, so the burden might not be so persistent. On (2): the RL scaling data is thin, and there’s likely been substantial compute efficiency progress in RL since o1 and o3.

I. What I agree with

I agree with Toby that for tasks that models can solve at all by increasing inference compute, it frequently seems more efficient to scale inference compute than to increase RL compute.1

Scaling reinforcement learning also makes it possible to perform new tasks the model could not achieve before with any amount of test-time compute (for example, many METR tasks). However, as Toby argues, RL unlocks these new tasks in large part by allowing the model to productively use longer outputs (chain of thought, tool calls, or writing) when completing them. Often, these harder tasks inherently require more steps to complete, and just scaling reinforcement learning does not particularly seem to make more steps happen within individual forward passes (see also this related post by Ryan Greenblatt).

Thus, to solve these new, harder tasks with your newly RL-scaled model, you have to pay a large inference cost — a variable cost that unlike training costs is not amortized by serving more users.

II. Fixed-capability costs fall fast

Toby suggests that with RL scaling approaching its limits, inference scaling is all that remains2, and inference scaling gives models more time to think rather than making them smarter per step. He argues this means the compute scaling that has driven recent AI progress will substantially weaken, while also imposing persistent per-use costs.

I agree that per-use costs can be significant in the short run3, but I’m not convinced they’re persistent, since the price of inference to reach a given capability level drops rapidly. In a related post, Toby looks at the cost of running models on the METR suite, and how that has changed as time horizons have increased. However, all the models considered in this analysis were state-of-the-art at release, so this analysis does not account for how much cheaper inference can become.

First, individual forward passes can become less expensive over time. Improvements to model training mean that smaller models can match the capability of earlier larger ones. Distillation is a salient example: once a frontier model can generate high-quality reasoning traces, you can train smaller, cheaper models to imitate those traces. On top of that, a steady stream of algorithmic improvements in inference efficiency (e.g. speculative decoding, paged attention, sparse attention, offloading or compressing the KV-cache, etc.) all reduce the cost per token.

At the same time, over time models can reach the same level of capabilities while needing to do fewer forward passes. Models can be trained to reason more concisely: Anthropic, for instance, substantially reduced the verbosity of Claude’s reasoning between Claude Sonnet 3.7 and Claude Sonnet 44.

Hardware improvements also help: the cost per FLOP decreases with each new generation of GPU. Combined with the algorithmic gains above, we can see the net effect on concrete tasks. On FrontierMath, reaching roughly 27% accuracy required about 43 million output tokens with o4-mini with high reasoning effort in April 2025, but only about 5 million tokens with GPT-5.2 with low reasoning effort in December 2025. Even accounting for the difference in price per output token, that’s roughly a 3x cost reduction over eight months. Overall, the trend seems to be very roughly a 5–10x cost reduction per year for reaching a given capability level5. Concretely, suppose the first AI that can perfectly replicate the web interface for a complex economic model can only do so for $50,000. While that is a high initial price, if the most aggressive cost reductions hold, it would become $5,000 a year later, and $500 after two years.

This changes the economic picture: even if it is initially costly for a user to reach a given capability level, this gets much cheaper over time. Nevertheless, this decrease might slow down in the future. There is likely a number of parameters below which models are simply too small to have strong general agentic capabilities regardless of how they are distilled. And heavily distilled models do seem to be more brittle overall. The fast cost reductions we observe might partly be an artifact of measuring capabilities through benchmarks, where distilled models tend to perform disproportionately well. That said, even with these caveats, 5–10x per year is a very fast trend. Overall, this makes me more interested in tracking the capabilities of smaller models and trends in falling inference costs: stay tuned as we will have more rigorous analysis on this soon!

III. The returns to RL scaling might be higher

Toby’s core estimate comes from comparing the two panels in OpenAI’s original o1 announcement chart. Both panels show performance on AIME with a logarithmic x-axis spanning roughly two orders of magnitude (100x). The left panel shows RL training scaling, while the right panel shows inference scaling. Toby observes that the slope of the RL panel is roughly half that of the inference panel: 100x more inference takes you from around 20% to around 80%, while 100x more RL training only takes you from around 33% to around 66%. At that rate, matching the jump from 20% to 80% would require 10,000x more RL compute. Toby then checks this against the o3 training curve and the o1-to-o3 and o3-to-GPT-5 comparisons, which are broadly consistent.

This is an interesting observation, but I find it hard to draw strong conclusions from it. The x-axis numbers are removed, we’re reading slopes off a small number of data points, and scaling trends are frequently sensitive to details we don’t have access to from the outside.

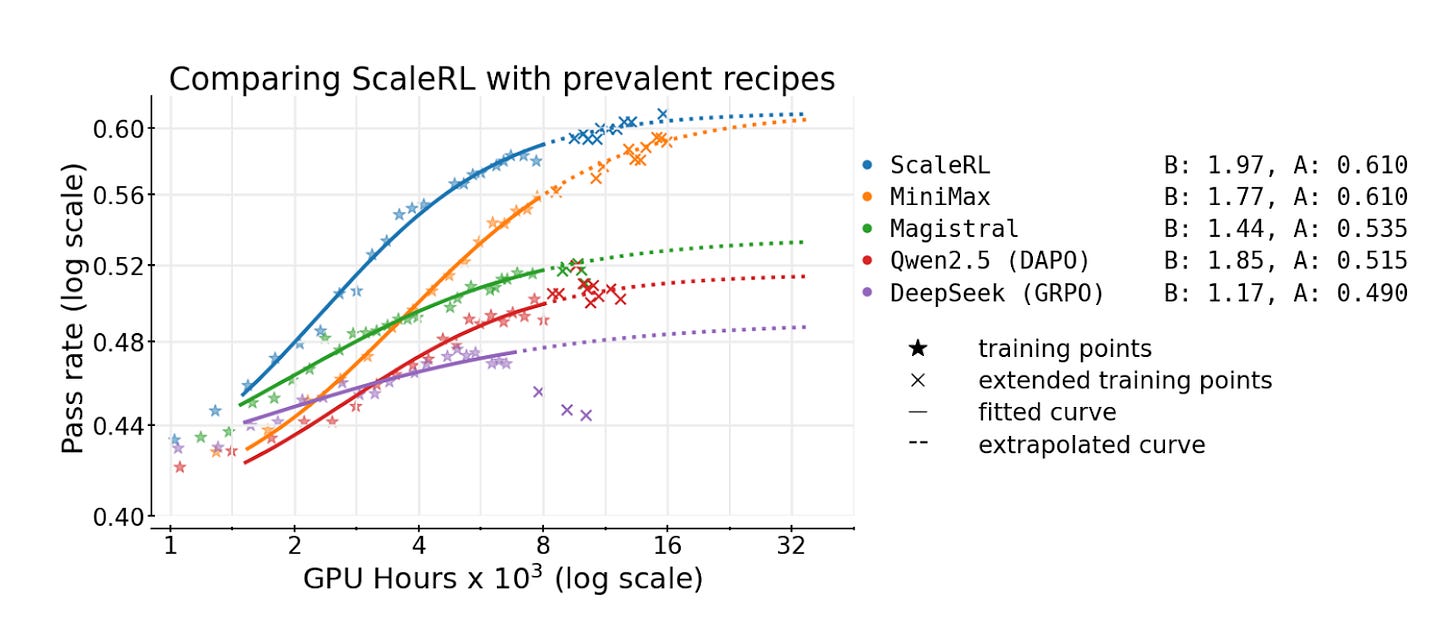

More importantly, algorithmic progress can shift a given RL scaling curve substantially. For example, in Figure 2 of this paper studying RL scaling laws, Scaled RL achieves more than twice the slope of GRPO on comparable benchmarks (see figure below), including when the y-axis is linear while the x-axis is logarithmic. This is at much lower compute scales than o1 and o3, so it’s not directly comparable, but it illustrates how much the efficiency of RL training can vary with the algorithm.

It also makes sense to me that OpenAI wouldn’t have been laser-focused on maximizing RL compute efficiency in the early days of o1 and o3. RL compute was still a small fraction of total training cost, so the returns were good enough without needing to optimize compute aggressively. Since then, there’s likely been considerable algorithmic progress (in large part through better and more diverse RL tasks and environments), which likely improved the slope of RL scaling. Much of the effort since o1 and o3 has also gone into applying RL to new domains beyond math and coding, rather than pushing RL as far as possible within those two domains.

Conclusion

Toby's discussion of RL scaling versus inference scaling is useful, and the core observation that RL gains come largely with longer chains of thought is well-taken. But the picture he paints may overstate how much of a bottleneck this will be for AI progress. The cost to reach a given capability level falls fast, so the inference cost burden is more transient than it might appear from looking only at frontier models at launch. And the RL scaling data we have is still thin, so I would treat the 10,000x figure with a grain of salt. This has made me more interested in studying how quickly cheaper models catch up to frontier capability levels, and how inference costs for a fixed task decrease over time.

Thanks to Toby Ord, Ryan Greenblatt, Greg Burnham, Anson Ho, David Owen, Tao Lin and Josh You for helpful comments.

In fact, the returns to inference compute scaling might be even better than Toby mentions, since his estimates focus on increasing reasoning effort but mostly do not account for other ways of increasing inference compute, such as best-of-n sampling.

At least, unless or until there is a new paradigm of compute scaling.

As Ryan Greenblatt points out, even for these initial costs, it matters how they compare to the cost of humans solving the task.

Relatedly, single-forward-pass reasoning capabilities appear to be increasing exponentially (thanks to Greg Burnham for pointing this out). This also suggests that tasks that once required long chains of thought could be handled with much fewer tokens. Note that this trend does not seem to be driven by RL itself, and might trade off with the previous trend, to the extent that it requires larger models.

Our earlier data insight on inference price trends isn’t ideal evidence here, since it doesn’t account for reasoning models or tasks where longer outputs provide genuine value, and probably is unusually vulnerable to benchmark climbing/contamination.